What feathers can tell us: Summer internship with ANTSIE

My name is Elinor Baldwin, I’m an undergraduate at Durham University about to enter my final year of study in Geography (Bsc). I have been assisting on the ANTSIE project as a summer intern supervised by Prof. Erin McClymont (Durham University, ANTSIE PI), Ellie Honan (Durham University PhD) and Dr Ewan Wakefield (Durham University). During my 7-week internship I have been processing snow petrel and Antarctic petrel feathers from Svarthamaren (Antarctica) and subsampling them for genetic and stable isotope analysis- well over 300 samples!

Snow petrels and Antarctic petrels are impressive little seabirds who travel hundreds of kilometres to forage for food in the pack ice before returning to their inland and rocky breeding grounds. They are some of the very few bird species to have been spotted as remotely as the South Pole.

The feather samples were collected from both living and deceased individuals at Svarthamaren, Dronning Maud Land. This nunatak is home to the largest seabird colony in all of Antarctica. The ANTSIE team is going to be using the stable isotope composition of the feathers to understand the petrel diets, because the trophic level of prey foraged by an individual petrel can be detected by looking at the stable nitrogen isotope ratio, which increases by 3-4 ‰ moving up each trophic level. The stable carbon isotope ratio is useful for determining the location of foraging, as the value decreases towards the coast and poles. It’s with this information that we can track where the birds at the current colonies have been foraging, and what they’ve been eating. In turn, we hope that this will tell us a lot about the current sea ice environment.

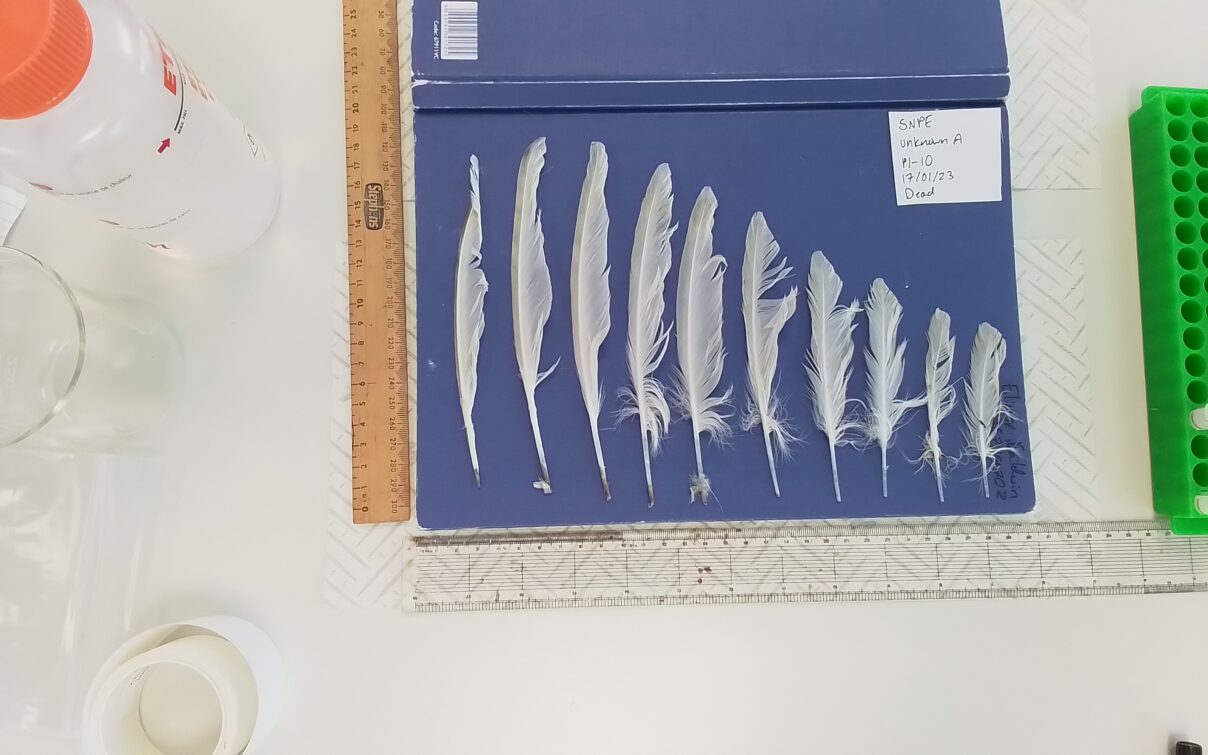

The feather samples were first prepared by using some very fiddly tweezers and scissors to carefully cut the calamus (the ‘tip’ or ‘quill’) of each feather into a vial for genetics testing. Because this part of the feather is where it is stuck in the bird, it has enough genetic material to sex the petrels and track the genetic lines within the colony.

I next went on to rinse each of the feathers to wash away any lipids or contaminants in preparation for stable isotope analysis. Both body and primary (flight) feathers grow in at different times due to the feather moult cycle- which is as long as 4 months in petrels. Because primary feathers grow in sequentially, our aim is to see a gradient of a bird’s diet by looking at the isotope content for each feather. In the coming weeks, the samples will be analysed in the Durham University Stable Isotope Lab and will be integrated into the ANTSIE research data.

It was an incredible opportunity to see how projects such as this work behind the scenes, and to even contribute myself! It has been an experience I will carry with me throughout my academic journey, and I can’t wait to start seeing the data.